(acknowledgement: Interview of Hong Kong Lawyer, publication of The Law Society of Hong Kong with Maurice Lee) (by Sonali Khemka)

There is a widely accepted theory that people are either left-brained or right-brained, meaning that one side of their brain is dominant. If you are mostly analytical and methodical in your thinking, you are said to be left-brained. If you tend to be more creative or artistic, you are thought to be right-brained. In Maurice Lee’s case however, the equal dominance of both sides has shaped him into the person he is today – a lawyer with the soul of an artist.

Writing Right

Lee enjoyed writing from as early as his teenage years, when he would take part in and win several writing competitions in high school. Encouraged by these victories, he applied for an after-school-scriptwriting class organised by Hong Kong TVB in 1978 – a class that only had twenty spots and over 3,000 applicants. At the age of seventeen and still in high school, Lee managed to bag a place as the youngest member of the class. “The classes were intense. They were held five times a week in the evenings and for three hours each,” he recalls. His immense enjoyment of the activity and aptitude for it led him to not only complete the course but also work part-time as a scriptwriter for TVB for few years after graduating from high school. At the time, his heart was set on becoming a professional scriptwriter or director.

However, the left side of his brain nudged at this point and Lee was tempted to pursue a university degree and career that was more academically sound and commercially viable. “My family told me that if you are in the creative field in the early 80s, you will face a very rocky path with many ups and downs. But if you are a lawyer, you have a safe landing,” he shares. After an internal battle between the left and right side of his brain, Lee eventually accepted his place in The University of Hong Kong’s School of Law. Not keen on giving up on his creative side, he continued working as a part-time scriptwriter for TVB throughout his four years in law school, focusing primarily on hour-long dramas and eventually switching to comedy. “I was good at writing dramas, but the producer told me I was not emotionally mature for the material in the drama shows,” he recalls amusingly. “I wasn’t at the appropriate age to write about passionate love affairs and dramatic struggles, so I switched to comedy,” he adds.

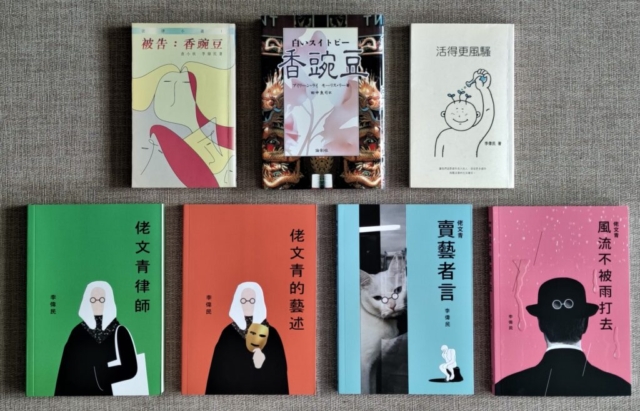

Lee’s creative career has taken different shapes and forms – a result of his willingness to not over plan and make the most of any worthy opportunity. In the mid-1980s, he wrote as a columnist for local newspapers, contributing 500-word prose pieces in Chinese on various topics and in the 1990s, Lee even garnered a fair amount of fame as a program host for a talk show for Commercial Radio Hong Kong. Around the same time, he was invited to write fiction literature by Cosmos Books and channeled his very own John Grisham by opting to write legal fictions. His present creative career, which commenced around six years ago, stems from an invitation from two online news platforms – HK01 and Orange News – to write critiques on different forms of art and culture, varying from movies and plays to visual arts and cultural trends. He supplements this with his own Facebook page, named “HKArtMan” where he shares his views on the same in a personal capacity. In addition, Lee also takes on the role of performance organiser when time permits and has previously organised a play and a concert – something he believes Hong Kong is in more need of.

Hong Kong’s Art Scene

Lee believes that prior to the 2000s, the city’s art and cultural scene was plagued by apathy and was a severely overlooked area. In the 2000s, Lee feels the situation has improved but not enough. “There is more curiosity and awareness, but people do not do enough to support the development of art and culture. There is too much financial reliance on the government only,” he shares. “Hong Kong is in a serious need for rebranding,” he adds. “We are currently just a financial center – like Zurich or Luxembourg and relying too much on old industries like logistics and trading,” he explains. Lee envisions a Hong Kong that is on par with global cultural and financial hubs like London or New York City and believes moving towards intangible assets or intangible intellectual property such as the arts is crucial. “We need commercial energy to be put into the art and cultural circles and more money from private companies and investors. That way more people will feel encouraged to pursue artistic careers because they can earn a decent income, which will in turn drive Hong Kong’s art and cultural scene,” he shares. His ultimate dream is what he calls an “Art Economy for Hong Kong,” an environment whereby art becomes more than just a leisurely activity and can be pursued as a commercially viable career.

In order to help realise his vision for a more art-savvy Hong Kong, he plans on putting together a concert and a musical for export to the Greater Bay Area (GBA) next year. “If they are staged only in Hong Kong, there can be less than five shows. However, if I export them to eleven cities in the GBA region, I can stage sixty shows – it makes more sense as an economically sustainable activity,” he explains. Lee believes exporting Hong Kong’s artistic talent is key, if financial prosperity in the arts and cultures is to be achieved. He recalls Hong Kong’s former status as “Hollywood of the East”, a time when films made in the city were enjoyed fervently beyond the borders. Similarly, he is hopeful that other forms of home-made art will also someday be appreciated in different markets.

Critically Creative

For Lee himself, he is content with how his career and personality have shaped out to be. “People tell me as a lawyer I talk like an artist, and as an artist I talk like a lawyer,” he shares. “As a lawyer, I am more sentimental, humanitarian and expressive and as an artist, I always have a mental framework. Artists can be quite unorganised. I am very organised. I put bits and pieces under different headings and am good at fulfilling long-term artistic projects because as a lawyer you are always handling long term cases. You have to be systematic and strategic,” he explains.

Lee encourages lawyers to pursue a creative side too, albeit on a personal level – something he believes would only make them more professionally sought-after. “People think lawyers are checklist animals, I think they are more than that. There is a lot of creativeness and criticality involved in being a lawyer when we handle a case and we should keep those sides alive,” he shares. “There are two minds in demand nowadays – the creative mind and the critical mind. No matter what profession you are in, you should have both,” he adds. He is aware that evolving from executors who merely follow instructions to critical thinkers who ask questions and initiate change can cause adverse reactions – “People find this type of person to be very maa faan (annoying/troublesome), they know too much and ask too much,” he shares with a grin. “But it is important to stand out, both minds will help each other,” he adds.

As a consumer or spectator, his favourite types or forms of art include ballet, paintings by American artist Edward Hopper and the diminishing art of Cantonese opera. “I admire ballet because it is so physically challenging and difficult. I like paintings by Edward Hopper because they make me feel sad – his pieces are very poignant. And I treasure Cantonese opera because it is sadly disappearing. They use old Shakespearean style Chinese dialect which might someday vanish completely,” he explains.

Having enjoyed a rewarding career so far, with ups and downs, with legal wins and creative commendations in abundance, Lee has a particular memory that still lingers vividly. “Fifteen years ago, I was the Vice-Chairman of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council. At that time, the famous movie director Johnnie To and I organised the first outdoor media art exhibition outside the Hong Kong Cultural Centre in Tsim Sha Tsui. The idea was to do some artistic projections on the external wall of the cultural centre and these projections were shut off by 11:00pm. I was at the exhibition till closing on the first day when a young boy came up to me, shortly past 11:00pm. He was 14-15 years old and he begged me to allow him into the exhibition area. He said his family is poor and he works at McDonalds at night. He lives in Tai Po and has come all the way to Tsim Sha Tsui to view the exhibition because he was so interested in what it might be like,” Lee recalls. Moved by the young boy’s passion and determination, he allowed him in as an exception. Till this date, Lee wonders what became of that young boy and whether he ended up pursuing something artistic. “I was so touched and amazed and I wonder how many boys and girls or men and women in Hong Kong have that kind of passion for something non-commercial, something artistic and spiritual,” he muses. If it fortunately turns out to be that the boy is one of our readers, Lee would be delighted to hear from you.

The Law Society of Hong Kong Journal

This article can also be found at the following sites: