There are different kinds of puppets for a show and they can talk, sing and dance to amuse: glove puppet, rod puppet, shadow puppet, finger puppet and string-operated puppet. In Hong Kong, rod puppets and string-operated puppets (sometimes known as marionette) were once popular. Only a handful of very old artists still work in the trade. When they are gone, there is no contrivance on earth which can make puppet shows appear again in Hong Kong…

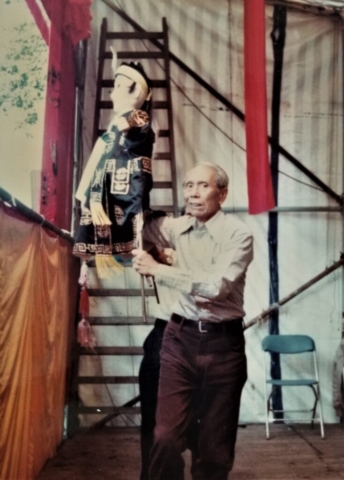

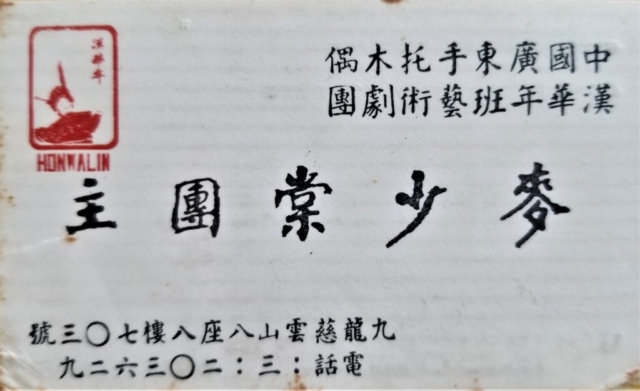

Man dies but glory lives. This is true not only for soldiers—but also artists. Mak Siu Tong, the greatest puppet master of Hong Kong was born in 1907 and passed away in 1987. He had enjoyed 80 years of fame. Mak learnt puppet art from his uncle in Guangdong Province of China when he was 15. After World War II, he came to Hong Kong to seek refuge. In China, he was a puppet hero. Poor in Hong Kong, he lost his backslappers who are fading out. Mak Siu Tong had to start his career again. He was multi-talented and could control rod puppets, do playwriting and sing. He also performed in Cantonese opera but took up both male and female roles when it was considered by women to be a disgrace to perform publicly in those days. In grave need of money to support his wife & daughter, Mak found the job of a handyman in a factory in Kowloon. Being a ‘nobody’ worker, he could ask for a day off at anytime to pursue his journey for puppet stardom. He accepted offers to perform in the different parts of Hong Kong: remote villages, outdoor playgrounds, party restaurants, temples and theatres. Such performances were usually badly paid. His wife always said, “My dear, please forget about puppets. Find a long-term job which can feed your family well!” Such conversations about reality and unreality normally ended in silence. Puppet shows were the only thing that can make Mak feel alive and passionate. He told his friends, “Puppet art is my life. No matter rich or poor, I must continue at any cost!”

The ‘self-image’ is the key to human dignity. Despite being a worker in a filthy factory, Mak wanted to look like a star when he appeared in the public as a proud and well-dressed puppet artist: a neatly ironed shirt, a pair of blue jeans, a scarf, a painter cap and sometimes a trench coat. He was confident about his profession. Although Mak was fond of cured and braised fatty pork, he tried to eat as little as possible in order to keep his slim body shape.

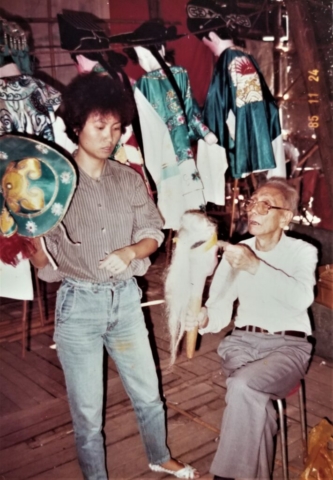

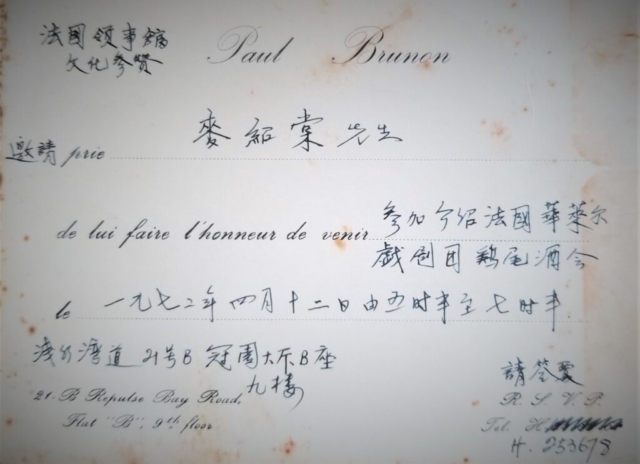

In his old age, Mak was trying very hard to find an art apprentice to continue puppet art in Hong Kong. He was sad to see puppet shows being abandoned. For him, the disappearing of puppets meant the disappearing of humanity without kindness or taste. As expected, no young boy or girl would respond to his invitation as doing puppet shows as a career would imply extreme poverty which was something to be ashamed of in an expensive city like Hong Kong. Even Mak’s daughter Connie turned down her father’s suggestion that she could become a puppet master. In 1987, before Mak died of scurvy in a hospital, he told Connie, “Most people want a lavish funeral. I want it too. I want my puppets, tools and scripts to be kept and stored up. For me, this is already a lavish farewell!” Connie did keep her promise. Since 1987, she has been keeping Mak’s puppets and meaningful things in a storeroom in Mei Lam Estate, a public housing estate in Shatin where Mak Siu Tong lived because his humble income was not good enough to allow him to buy a private home. Among all the ‘treasures’ of Mak, there were a few rod puppets of several hundred years of age and likely made in the Pearl River Delta region of China. The puppet rods were hollow inside. The eyes and mouth of the puppet were controlled by small sticks. At the request of a French collector in the 70s, Mak went to China to look for puppets of historical value. After shipping the purchased puppets to Europe, the man bequeathed a few to Mak.

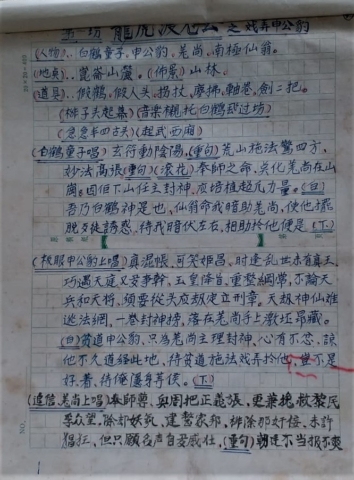

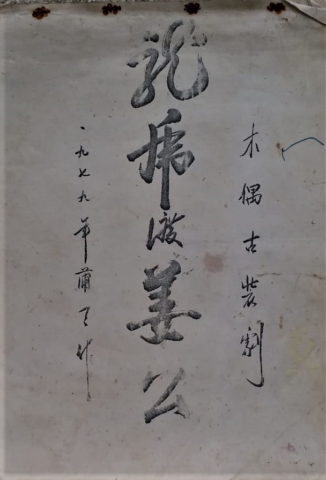

Just a while ago, Connie contacted me and said, “The landlord, Hong Kong Housing Authority, will terminate the lease of the storeroom. I cannot afford a commercial storage place. It is tragic that I will have to throw away my father’s belongings. I know his puppets and other possessions are culturally precious. Could you find a museum which is kind enough to take over the riches?” Without the slightest hesitation, I phoned Mr. Terence Cheung, curator of the Hong Kong Museum of History. He promptly went with his colleagues to Mei Lam Estate with me. They found quite a number of exceptional items and some of them would be acquired as museum collections after deliberations. I was attracted by a puppet opera script printed in the 1950s.

Poverty entails hardship and stress. Even now, many artists are poor. People are happy to pay for new clothing and good food but not art. Commercial sectors in Hong Kong seldom pride themselves on supporting and donating to art activities. It may be wrong to tell people to follow their dreams no matter what, because being a miserable artist is not an easy game. On the other hand, for those who are not troubled by the burden of making a living or the satisfaction of succeeding in art is far more important than money rewards, they should close their eyes and dig deep into art, like what Master Mak did.

Someone told me this: every time you do a good deed, you shine the light a little further into the dark. When you are gone, the light is going to keep on shining and will push the shadows back. The life of Mak Siu Tong must be a mixture of happiness and traumas. Yet, he did a good deed for the art of Hong Kong. The good deed I did for him and his legacies is like raising my hand in salute to a great artist who left us about 30 years ago. We miss such a wonderful master. When Mak Siu Tong disappeared, the puppet art of Guangdong became invisible in Hong Kong. It may be natural. I just meditate about it.

This article can also be found at the following sites: